Sea Trout/Brown Trout (Salmo trutta)

Key Findings

Introduction to sea trout

Sea trout are not a distinct species but a migratory form of brown trout. Due to a combination of genetic and environmental factors, they have adapted to live in both freshwater and saltwater habitats, migrating to the ocean to feed and returning to freshwater to spawn. This behavior, originally an adaptation to food scarcity, is what gives the sea trout its name. What distinguishes this species from other migratory fish in Scotland, such as the Atlantic salmon, is that they do not travel to distant feeding grounds. Instead, they remain in coastal or estuarine areas, generally no further than 80 km from the river in which they were born (Beamish, 2025).

The lifecycle of sea trout

The life cycle of sea trout begins with spawning between November and February, when females dig gravel nests, known as redds, to lay their eggs. Fertilised eggs hatch into alevins after a few months, depending on the water temperature. Alevins remain in the gravel, feeding on their yolk sacs before emerging as fry to establish territories and grow into parr. Parr are solitary and require sheltered habitats such as stones and plants in slow-moving streams and ditches. After one to three years in freshwater, they transform into smolts in spring, developing a silvery appearance and adapting to saltwater before migrating to the sea. Adult sea trout feed in the sea or estuaries before returning to freshwater, often their birthplace, to spawn. Unlike Atlantic salmon, sea trout do not usually die after spawning, and around 75% will return to the sea after each spawn (Wild Trout Trust, 2025).

Threats to the species

Unlike Atlantic salmon, sea trout typically spawn in smaller coastal streams and tributaries of large rivers, rather than in the main river channels. These spawning grounds are often overlooked and seen as little more than ditches. In agricultural areas (which make up much of Scotland), river burns are frequently straightened and dredged for their gravel beds to improve drainage. This practice destroys much of the local vegetation, reducing cover and invertebrate production, which sea trout rely on for shelter and food. Like salmon, they are a cold-water species, sensitive to temperature fluctuations. The removal of vegetation exacerbates the impacts of climate change on their habitat. Man-made barriers, such as culverts and old weirs, also restrict the species by disrupting crucial migratory routes, fragmenting populations, and making them more vulnerable to small environmental changes (Scottish Wildlife Trust, 2025). Other threats to the species primarily stem from their marine environment, including trawling and dredging in coastal habitats, offshore wind development, water quality issues, and pollution (Freyhof, 2024), in addition to a reduction in important food sources such as sand eels (Beamish, 2025).

Status and population trends of Sea trout

Brown trout are found throughout Scotland, inhabiting headwater streams, lowland rivers, estuaries and some coastal marine waters (Scottish Wildlife Trust, 2025). Their wide distribution, shown in the image below, highlights their resilience as a species. Brown Trout was last assessed for the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species in 2022, receiving a classification as ‘Least Concern’ (Freyhof, 2024).

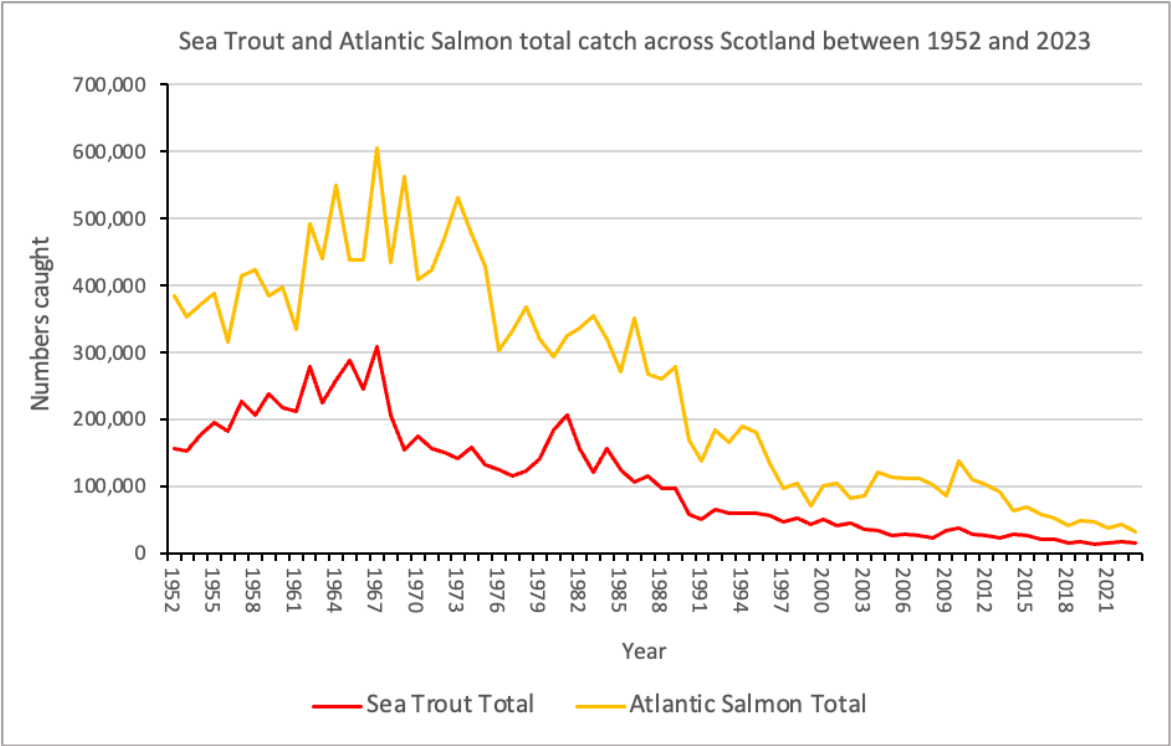

Sea trout however have undergone a significant decline over the years, as depicted in the graph below, which draws on data from Scottish fisheries statistics. The trend illustrates a consistent decrease similar to that of Atlantic salmon, suggesting that both species may be facing comparable threats. This decline has resulted in the sea trout being designated as one of the Scottish Wildlife Trust's priority species (Scottish Wildlife Trust, 2025).

The future of sea trout in Scotland

Neither brown nor sea trout receive significant protection under conservation legislation. While there is standardised protection against exploitation within fisheries, there is no comprehensive or definitive legal framework in place (NatureScot, 2023). However, both brown trout and sea trout are UK Biodiversity Action Plan priority fish species (JNCC, 2007) . The following actions have been identified to mitigate future widespread species loss (Beamish, 2025)

- The removal of in-river obstacles such as weirs or installation of fish passes to allow free passage.

- Regulation of land use in catchment areas to reduce nutrient runoff and siltation due to soil erosion.

- Improving water quality by addressing pollution and maintaining water quantity by addressing abstraction.

- Protecting sandeels through Marine Protected Areas or fisheries regulation.

Sea trout are experiencing the same population decline as Atlantic salmon. However, because they are a subspecies of brown trout, which has a stable population, conservation efforts for sea trout remain limited. To preserve their populations, stricter regulations and measures are needed to protect and improve known sea trout habitats.

Figure 1. Picture of a landed sea trout, taken from Scottish Wildlife Trust.

Figure 2. The Distribution of brown trout across the UK and Europe (IUCN, 2022)

Figure 3. Comparison of sea trout and Atlantic salmon total catch between 1952 and 2023, created by George Trantham using Scottish fisheries statistics.

Notes

Linked Information Sheets

Key Sources of Information

Scottish Environment LINK. (n.d.) Sea Trout.

Scottish Wildlife Trust. (2018) 'Turning the Tide for Scotland's Sea Trout'.

Wild Trout Trust. (n.d.). Sea Trout.

for, I. (2022). IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Salmo trutta.

Joint Nature Conservation Committee (2007) List of UK BAP Priority Marine Species.

NatureScot. (n.d.). Brown trout.

The Scottish Government (2024). Scottish salmon and sea trout fishery statistics 2023.

Reviewed on/by

13/01/2025 by George Trantham

13/01/2025 by Mariia Topol

Status

First Draft

To report errors, highlight new data, or discuss alternative interpretations, please complete the form below and we will aim to respond to you within 28 days

Contact us

Telephone: 07971149117

E-mail: ian.hay@stateofthecoast.scot

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.