Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar)

Key Findings

Introduction to Atlantic Salmon

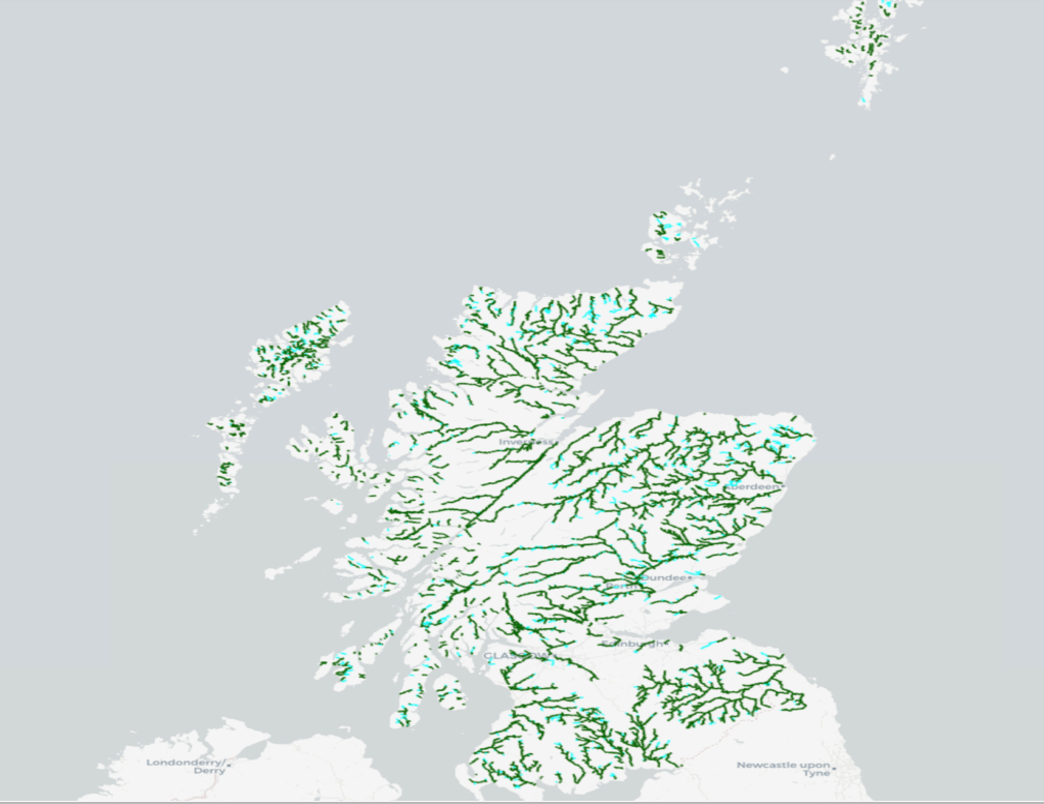

Wild Atlantic salmon are found in over 400 rivers across the country (Monteith, 2025), highlighted in the picture above. This species has long been integral to Scotland’s culture and traditions, symbolising both natural heritage and economic significance. Wild salmon fishing, both in rivers and along the coast, has been a key practice, vital not only to the economy but also to rural communities in Scotland. Beyond their economic value, wild salmon are deeply embedded in Scotland’s ecological and cultural identity, shaping the nation’s natural environment and human society for millions of years (Ashley, 2019) However, increased pressure on wild populations has led to a significant decline. In response, Scotland has become the largest producer of farmed Atlantic salmon in Europe and ranks third globally, following Norway and Chile (Best Fishes, 2025). The farmed salmon sector supports an extensive supply chain across the UK, sustaining around 3,600 businesses and more than 4,300 jobs (Ashley, 2019). Despite the growth of farmed salmon, the population of wild Atlantic salmon has decreased by approximately 40% over the past 40 years, highlighting the challenges faced by wild populations (Gov.scot, 2021).

Status and Trends of Wild Atlantic Salmon Populations in Scotland

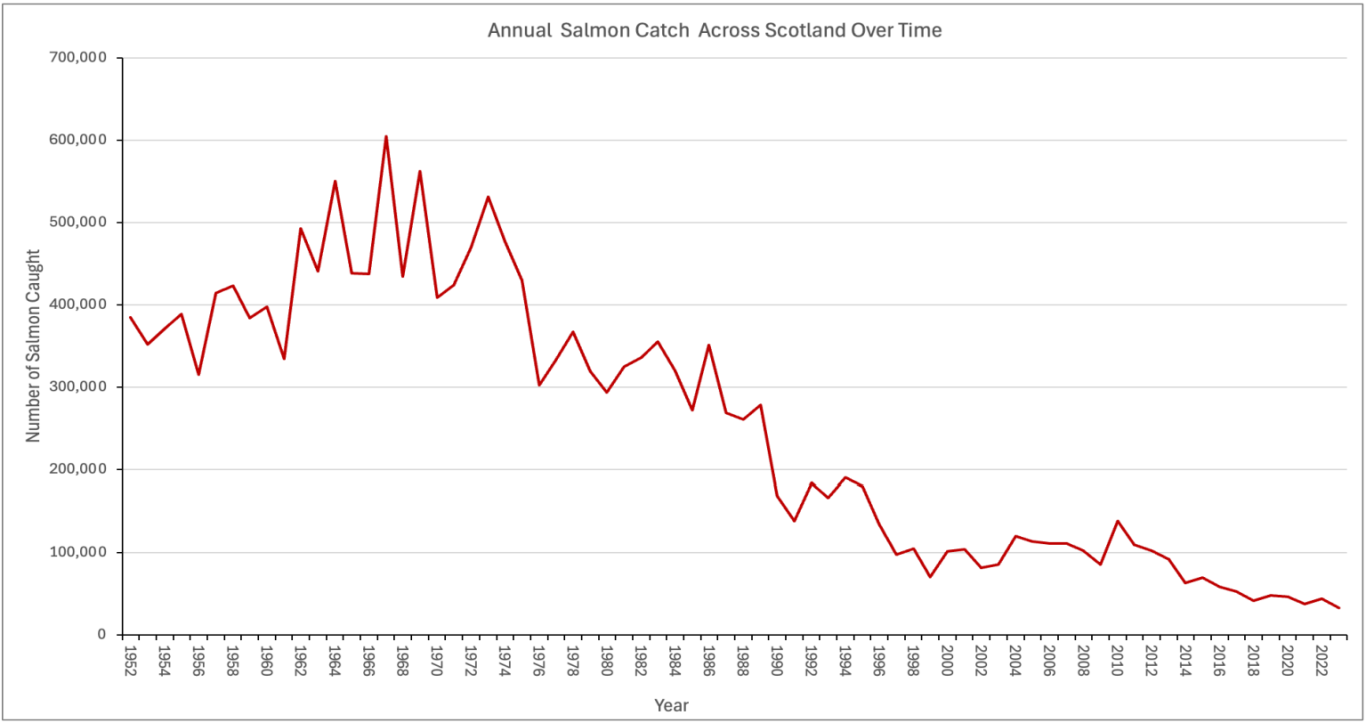

In 2023, the reported rod catch of wild Atlantic salmon totalled 32,477, marking the lowest figure since record-keeping began in 1952.This represents a 24% decline from 2022 and a 77% decrease compared to the previous five-year average (Gov.scot, 2023). The overall trend in salmon catches from 1952 to 2023, seen in the graph below, highlights a troubling decline for the species without significant intervention. In 2022, Atlantic salmon was assessed for the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species and classified as Near Threatened (Darwall, 2023). As numbers continue to decline annually in Scotland, this classification could worsen. Though the species is present in other countries around the world, the overall population is severely fragmented, putting the species further at risk.

Migratory Behaviours

Atlantic salmon begin their life in freshwater, hatching from eggs laid in gravel nests known as redds. Spawning typically occurs between October and February, with most adults dying afterward, though a few may survive to spawn again. The young fish, called alevins, remain in the gravel until they absorb their yolk sac and emerge as fry, about 3 cm long. These fry develop into parr, which stay in the river for two to three years, depending on water temperature and food availability. Once they reach about 12 cm, parr transform into smolts, adapted for survival at sea. Smolts migrate to the ocean in late spring, where they grow into post-smolts. Some return after one year as grilse, weighing 2 to 3 kg, while others remain at sea for up to three years, returning as larger multi-sea-winter salmon (NatureScot, 2023).

Threats to the species

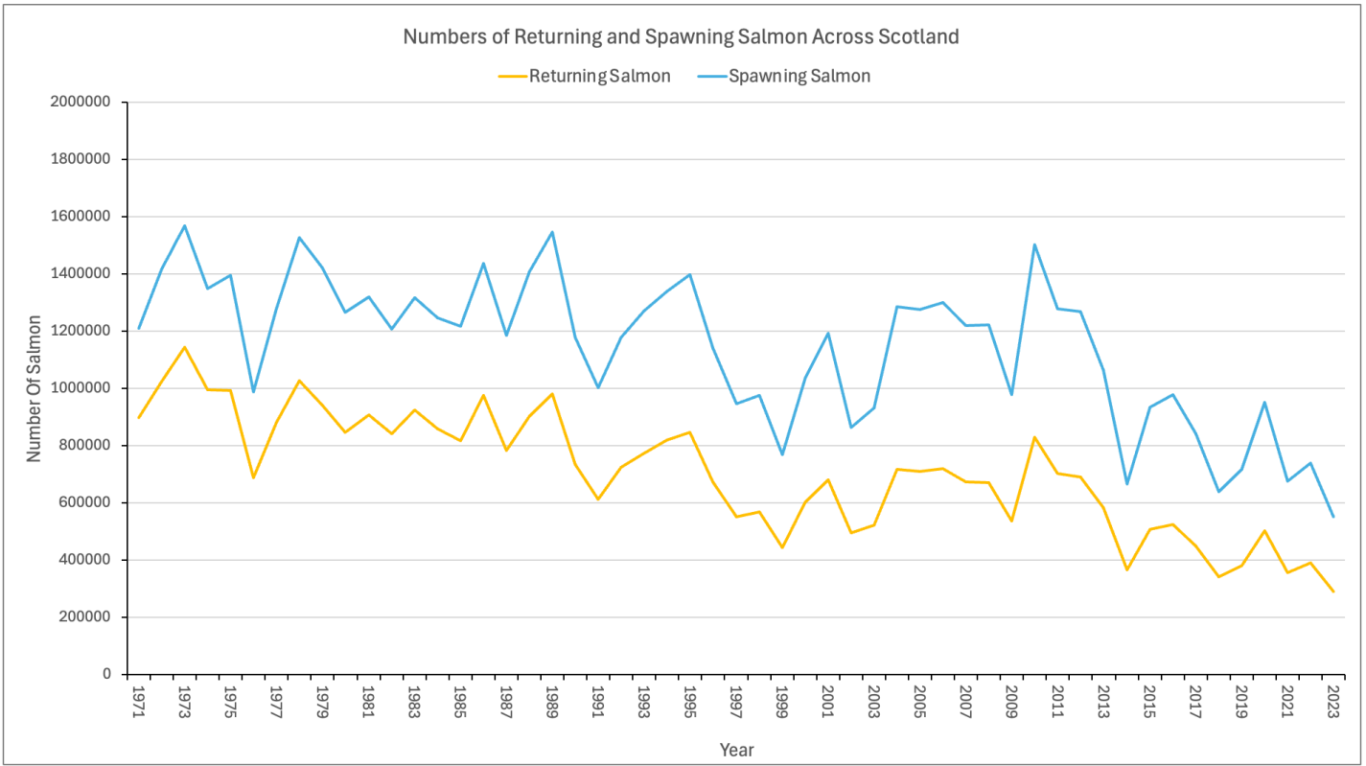

The migratory behaviors of Atlantic Salmon is a key factor in their vulnerability, with one of the most significant threats to their populations across Europe being man-made barriers, such as dams and weirs. These barriers block essential migratory routes, preventing salmon from reaching their spawning grounds. While the Scottish population of Atlantic Salmon faces fewer barriers compared to other regions, they remain a significant concern (White & Knights, 1997). The fragmentation caused by these barriers results in smaller populations, which are more vulnerable to interbreeding and a loss of genetic diversity, further heightening the risk of their decline. The graph below shows the returning and spawning rates of salmon in Scotland, which are seen to have steadily decreased from 1971 to 2023. This downward trend emphasises the ongoing challenges faced by salmon populations to both spawn and return to the region.

As a species adapted to cold water, salmon are particularly vulnerable to temperature fluctuations in rivers. With this said, they are facing increased risks driven by climate change. Warming oceans, the frequency and intensity of floods and droughts, rising sea levels, and ocean acidification are all known to disrupt key stages of their life cycle (NOAA, 2024). For instance, unusually warm spawning conditions and high river flows in 2016 contributed to a notable decline in juvenile survival (Gregory et al, 2020). Rising sea temperatures are also forcing migration routes further north, creating additional challenges for southern populations such as those here in Scotland, which may struggle to adapt to the longer journeys required to find adequate feeding grounds (Mills and Sheehan, 2023). In 2018, a particularly warm summer saw nearly 70% of Scotland’s rivers reach temperatures capable of causing stress to salmon, underscoring the urgency of mitigating these environmental impacts (Gov.scot, 2021).

Scotland has set ambitious renewable energy targets, aiming to significantly reduce its carbon emissions and transition to cleaner energy sources. These goals include plans to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2045, through substantially increasing the use of renewable energy relative to non-renewable energy sources (Gov.scot, 2023) The impacts of offshore energy developments, including oil and wind, add another layer of challenges for the wild Atlantic salmon, as the construction and presence of this infrastructure can disrupt their migration routes. Offshore wind projects, particularly those with export cables connecting to the mainland, often intersect with critical migratory pathways, potentially hindering their movement and survival (Honkanen et al., 2024). This makes climate change a double-edged sword for the species, as it amplifies existing threats while introducing new ones. Other threats to the species include increasing pollution, declining insect populations caused by infrastructure development, and growing concerns over the introduction of invasive non-native Pink salmon, which could outcompete the native population.

The future of Wild Atlantic Salmon in Scotland

To address the threats facing wild Atlantic salmon, the Scottish government has developed a comprehensive action plan aimed at improving the species' chances of survival. The core objectives of this plan include the ‘Wild Salmon Strategy’, which focuses on tackling the various pressures on the species across rivers, coastal areas and the open sea. The Strategy Implementation Plan for 2023-2028 outlines the collective actions required from government bodies, businesses, and charitable sectors to support conservation efforts (Gov.scot, 2022)

Key initiatives include:

- Improving River Conditions: Actions such as enhancing water quality at wastewater treatment plants, addressing pollution from agriculture and forestry, restoring peatlands, and expanding protected areas to support salmon habitats.

- Removing Migration Barriers: Efforts are underway to ease or remove over 150 barriers, including weirs and culverts, to restore access to critical spawning grounds.

- Predator and Invasive Species Management: Research and licensing efforts focus on reducing predation from seals and birds while managing invasive species and enhancing biosecurity measures.

- Marine and Coastal Protections: Strategies involve monitoring salmon migration patterns, minimizing the impact of marine developments, managing interactions with fish farming, and safeguarding key species in the food web.

- International Collaboration: Partnerships with organizations like NASCO are advancing global research, regulations, and the sharing of best practices to reduce salmon mortality worldwide.

- Policy Modernisation: A thorough review of existing policies aims to strengthen salmon protection and secure sustainable investments in river ecosystems.

Despite these efforts, the future of Atlantic salmon remains uncertain. Continued pressure from environmental and human-induced factors poses significant challenges, making sustained and adaptive conservation critical for their survival.

Figure 1. Scottish Salmon Rivers © Marine Scotland

Figure 2. Total number of wild salmon caught annually between 1952-2023 created by George Trantham using data from Scottish Salmon Fishery Statistics 2023.

Figure 3. Number of spawning and returning salmon in Scotland (1971-2023), created by George Trantham using data from Scottish Salmon Fishery Statistics 2023.

Notes

Linked Information Sheets

Key Sources of Information

Montieth, J. (2022). Jock Monteith. Complete Guide to Fishing for Salmon

Ashley, K. (n.d.). Wild Salmon. Scottish Parliament Reports.

Best Fishes. (2018). Scottish Salmon Farming - Best Fishes.

www.gov.scot. (n.d.). Conserving wild salmon.

The Scottish Government (2024). Scottish salmon and sea trout fishery statistics 2023.

William Darwall (IUCN (2022). IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Salmo salar.

Scottish Natural Heritage. (2017). Atlantic salmon.

NOAA Fisheries (2024). Climate Change Escalates Threats to Species in the Spotlight.

www.gov.scot. (n.d.). Scotland River Temperature Monitoring Network (SRTMN).

The Scottish Government (2024). Offshore wind - diadromous fish: review - January 2024.

Reviewed on/by

13/01/2025 by George Trantham

13/01/2025 by Mariia Topol

Status

First Draft

To report errors, highlight new data, or discuss alternative interpretations, please complete the form below and we will aim to respond to you within 28 days

Contact us

Telephone: 07971149117

E-mail: ian.hay@stateofthecoast.scot

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.