The Decline of Snow in Scotland

Key Findings

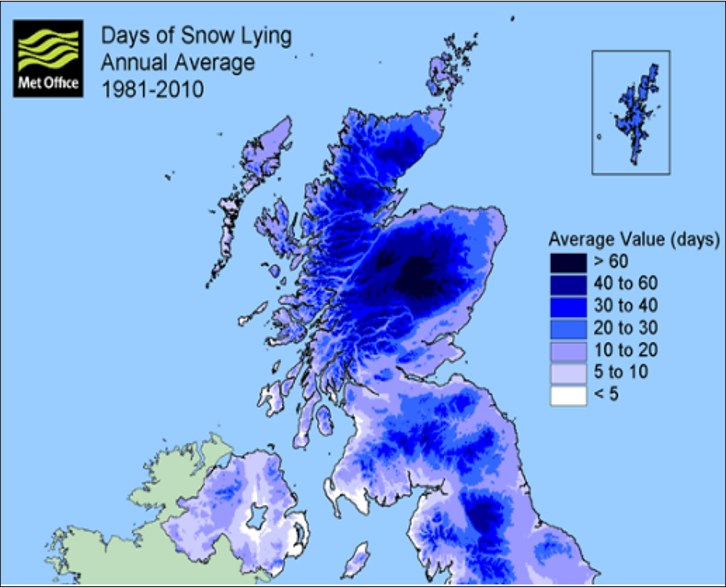

Snow-topped peaks are some of Scotland’s most iconic imagery, found up and down the country from the Borders to the Highlands. The snowiest location of the lot is the Cairngorms of Aberdeenshire, receiving more than 60 days of lying snow (fig, 1) and around 76 days of snowfall per year (Met Office, 2019).

Unfortunately, it may not be long until snow becomes a rarity across all of Scotland. With global warming firmly underway, the people and ecosystems depending on snow are likely to be hit hard in coming years.

Global Trends:

Snow and ice decline is perhaps the most straightforward of all climate change effects - increasing temperatures means snow and ice melt faster, while snow falls less regularly*. As such, more or less all global metrics of snow and ice are declining:

- Sea ice is decreasing at 0.51 million km³ per decade (NOAA, 2024)

- 265 billion metric tonnes of ice is lost per year from the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets combined (EPA, 2024)

- Having been shrinking overall since the 1970s (EPA, 2025), nearly half of the world’s glaciers are expected to have melted by 2100 under current warming trends (Dunne, 2023)

- Should the planet experience the worst-case emissions scenario RCP 8.5, around 77% (+/- 6%) of near-surface permafrost will be lost (Guo et al, 2023)

- Between 2000 and 2023, global snow cover declined by 5.12% (Young, 2023)

*Of course, climate change is ever entirely straightforward – increased water in the atmosphere due to warmer temperatures means certain areas with very cold conditions, e.g. the North of Russia, may expect an increase in snow (Quante et al, 2021). But, for most of the world, this generalisation holds.

Scottish Trends:

A key characteristic of snowfall in Scotland is interannual variability, with regular, natural year on year fluctuations in the volume of snow that falls (Rivington et al, 2019). Above this interannual variability however sits a clear overarching trend of snow reduction, in line with the wider world.

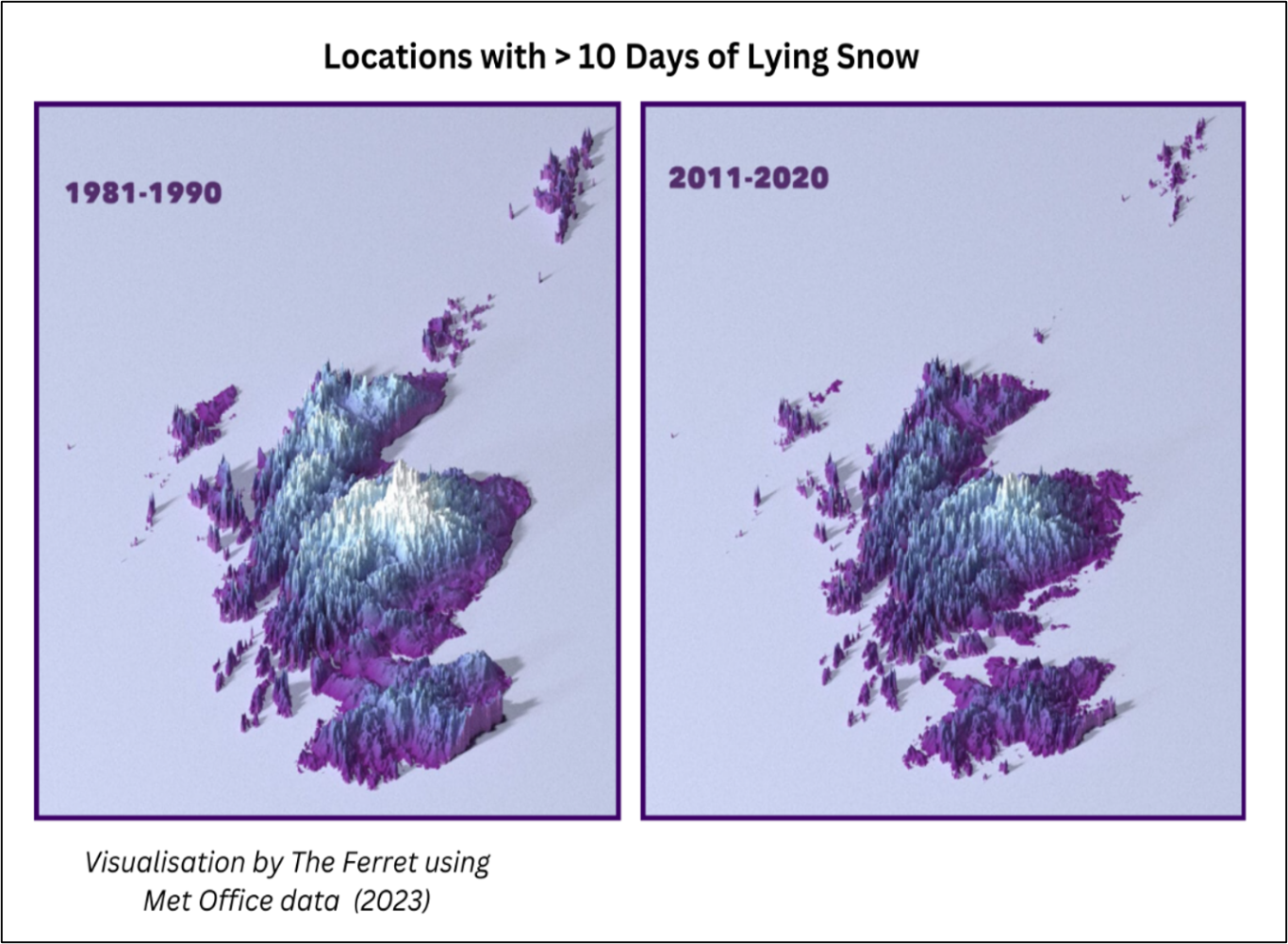

It is thought that a decline in both snowfall and lying snow has been ongoing for some time in Scotland (Rivington et al, 2019). This decline is visualised in figure 2, showing a clear reduction in places where snow lies for more than 10 days annually. Spracklen and Spracklen (2023) find the persistence of snow beyond winter to have ‘significantly declined’ between 1984 and 2022, while the average days of snowcover in 1990-2010 were thought to have reduced by 20-30 days in comparison with 1960-1980.

In the future, it is thought these trends will only worsen. Rivington et al (2019) explain that with temperatures now cooling later in winter, and warming earlier in spring, the snow season in Scotland is becoming ever more constrained. They estimate that by 2040-2050 snow cover on the Cairngorms will be in rapid decline, and by 2050-2080 some years may see no snow on the mountain range at all.

It is important to note that snowfall will not entirely disappear from Scotland. Extreme, short-lived snowfall events are likely to continue, as the generally warmer temperatures mean the air is humid enough to produce snow in snaps of cold weather (Quante et al, 2021).

Environmental Effects:

Scotland is home to many rare mountain flora and fauna, adapted over millennia to persistent snowy conditions. Without such snows, many species will struggle to survive and could be lost forever as a result. The ephemeral, intermittent snow events that are set to continue will not be enough to support these mountainous ecosystems.

Scots Pine saplings for example benefit from a thick snow layer, recieving insulation from harsh winter temperatures (Vuosku et al, 2022), while Rock Ptarmigans rely on winter snow for camouflage in their bright white plumage (Imperio et al, 2013). Reduced snow cover may also promote freeze and thaw cycles within mountain soils, resulting in nutrient leaching and the release of sequestered carbon (Rivington et al, 2019). Even human settlements could be severely affected, with rural communities often relying on river and groundwater flows fed by mountain snow (Simmonds et al, 2022).

To learn more about the increasing temperatures driving these changes in snowfall, please see our various pages on temperature trends in Scotland.

Fig. 1: Annual Average Days of Lying Snow for 1981-2010 - Retrieved from Rivington and Spencer (2020) with data from the Met Office.

Fig. 2: Change in locations which experience more than 10 days of lying snow annually - 1981-1990 average compared to 2011-2020 average. Visualisation by the Ferret (2023) using Met Office data.

Notes

None

Linked Information Sheets

Key sources of Information

Dunne (2023) Half of world’s glaciers to ‘disappear’ with 1.5C of global warming

EPA (2025) Climate Change Indicators: Glaciers

EPA (2024) Climate Change Indicators: Snow and Ice

NOAA (2024) Global Snow and Ice Report December 2024

Quante et al (2021) Regions of intensification of extreme snowfall under future warming

Simmonds et al (2022) A review of interacting natural hazards and cascading impacts in Scotland

The Ferret (2023) Visualised: Scotland’s changing snow cover

Young (2023) Global and Regional Snow Cover Decline: 2000-2022

Reviewed on/by

Status

First Draft

To report errors, highlight new data, or discuss alternative interpretations, please complete the form below and we will aim to respond to you within 28 days

Contact us

Telephone: 07971149117

E-mail: ian.hay@stateofthecoast.scot

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.